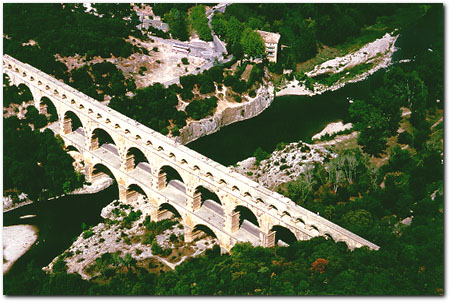

Pont du Gard

[A ‘plate’ question in 1980, 1985, 1990 and 1998]

This is the first of the civic monuments we are looking at. It is a very famous ______________ ___________ near the city of Nimes in the south of France.

Date: c19BC (Probably Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, a good friend and also the son-in-law of the emperor Augustus, supervised its construction and he was in the area at this time.)

Type: architecture:

aqueduct bridge

Height: 49 m (48.77m exactly and equivalent to an 18 storey building. This is the highest of all aqueduct bridges built by the Romans.)

Length: 275

m

Material: conchitic ____________, quarried locally, pale gold in

colour and fairly rough in texture

Location: 21 km NE of Nimes, one of the most important Roman provincial cities by the first century BC

Purpose: to carry water across the valley of the river Gardon, being part of a predominantly underground water pipeline from the Vauclusian Spring at Uzes, about 50 km from the city of Nimes

Architectural achievements

·

The engineering

techniques used to handle such great blocks of stone

·

Sufficient

strength to bear the weight of the stone and water above

·

The least

resistance to wind and river current

·

The critical

slope enabling the correct rate of flow of water over a great distance

Roman architectural techniques are known to us thanks to a Roman architect Vitruvius who wrote a book on architecture in the 1st century BC, in which he described the state of the art of architecture at this time as well as basic rules, working methods, and materials used.

How did it come

to be built?

The Roman army (under the command of _____________) had waged war against the Gauls from 59-49BC. Once Augustus Caesar became Emperor, he was keen to project the image of Rome as that of a nation bringing ________ – pax Romana – and with it improvements in living conditions. For Nimes, this meant a better water supply, for the spring within its walls was proving inadequate and the Romans would have been keen to demonstrate the advantages which living under their rule could bring. There was local stone to use, there were Roman ________ engineers who had the knowledge to design such a great construction, and thousands of men for labour - local Gallic slaves to assist the soldiers. Augustus also beautified the city of Nimes by building ramparts (city defences), the temple of Diana and the Maison Carree, the last of which we shall study soon.

Description

The conduit

(water pipe) is on the top of the single row of 35 small arches and the water

inside fell at a __________ of 1:3000.

The use of __________ adds strength to the building, enabling a minimum

of resistance to wind but sufficient strength to support the combined weight of

a lined and covered conduit and the water which used to pass through it. The

whole structure has a slight convexity, intended to counteract the harmful

effects of the current.

The middle row has three rows of 11 arches, while the bottom level of four rows of 6 very wide arches spanned the river beneath. The spans of the central arches in the lower two rows are large – 24.5 metres, (and in the top row above them there are four small arches) while the others are 15.5 metres (above which are three small arches). This wider span enables a ____________ of resistance being offered to the river currents, especially at times of flooding, and the prow-shaped piers at the base of the lower row of arches help in this regard too. The piers, completely submerged in flood but dry for most of the year, are at a slight angle to, rather than perpendicular to the current. The foundations were built into the rock.

B_________ projecting from the inner faces of the arches supported timber centering (alternative term: trusses) during the construction of the arch. These timber frames were reused on each parallel arch, a considerable economy. The bosses on the piers were for scaffolding. The fact that the bosses remained projecting would have enabled temporary scaffolding to be erected in the event of repairs.

The water conduit at the top was covered with _____________ to prevent natural or malicious fouling of the city’s water supply. Because limestone is naturally porous, the conduit was lined (40cm thick) with 2 or 3 layers of fine cement and ‘rubberised’ paint, called maltha. This made the passage of the water smooth, as well as the conduit becoming watertight. Lime deposits from the many years of water passing through gradually and considerably narrowed the walls of the channel. (See the illustration of a cross-section of the channel).

Vitruvius’ Roman cement

recipe:

Lime is

obtained by heating white stones or pebbles, and lime so obtained from porous

rock is preferable for coatings. “When the lime is slaked, it should be mixed

as follows: one part lime to three parts cave sand or two parts river or sea

sand; these are the proper proportions of this mixture which will be even

better if to the sea or river sand a third part of broken or crushed tile is

added.”

Pliny the Elder’s recipe for

maltha:

The maltha

is prepared with lumps of lime slaked in wine.

Here is the recipe: “This lime is ground into pork fat and figs, and two

layers are applied. Of all coatings,

this is the most durable; it is harder than the rock. Before applying the maltha, the wall is rubbed with oil.”

Preparation for and methods

of Construction

Military surveyors prepared the line of construction,

using the chorobate, a type of ___________, with four plumb lines attached.

The stone was quarried into squared blocks at

quarries very close by, still being worked, on the left bank of the Gardon in

the municipality of Vers. Large blocks were cut using wedges. Holes would first

be drilled in a row in the stone using a bow-drill and wooden wedge-shaped

blocks were hammered in. These w_______

were then soaked with water so that they swelled and split the rock. Some blocks of stone could be sawn using

bronze or iron blades, fed with sand to wear away the rock. When the stone had

been quarried, it might have been left to weather to make it smoother, before

it was used for building.

Prefabrication

Numerals have been found marked onto the blocks. These described the ________ in which they were to be installed and now are, e.g. FRD IV, meaning frons dextra IV, or the fourth block in the arch on the right façade. This care suggests that the stones were worked in the quarry to make transport and installation more efficient, and to reduce the need for shaping work at the construction site.

Transport of the quarried stone to the

______________ site was probably by oxen.

Once there, the final shape of each stone could easily be chiselled to

refine the shape, as conchitic limestone is friable.

Construction machines

were used to

put the stones in place. The piers and arches on the lower two levels were made

up of blocks of up to 2 cubic metres and weighing approximately 6 tonnes. They

were lifted into place probably by a tripaston,

drum tripaston or polyspaston (see the

illustrations). The stones were not

___________ together; they remain in place as freestone, compressed and locked

together by gravity and force.

The arches were constructed as follows:

1. The piers were built, with protruding

bosses 35

2. Timber framework (centering) was

erected using the bosses. 11

3. The v__________ were placed on the

framework. 6

4. The keystone was put in position last

of all and the timber centering removed.

Organisation of

labour was

professionally directed with ____________ precision to a precise timetable,

co-ordinating the surveying, quarrying, cutting, building, and mixing maltha

and concrete to line the water channel.

Technical

aspects of the passage of water along the entire length of an aqueduct:

·

The channel sloped just enough for gravity to overcome

friction, and therefore the smoother the surface, the less slope was needed.

·

Variation of the gradient was used to speed up or slow down

water and aqueducts sometimes twisted and turned to gain length and sustain a

low gradient. The gradient of the Nimes aqueduct is inconsistent but it is

unclear whether this was due to the lack of precision of instruments of the

time, or whether it was intended, for example, to slow the water down before it

reached Nimes.

·

The crossing of bridges was a minor proportion of the length

of water channel. The rest could consist of underground conduits of stone, terra

cotta, wood and leather, and pipes of lead and bronze. Tunnels ran up to 15m

underground, and had shafts to the surface at intervals of about 70m to allow

inspection and cleaning and to prevent air locks.

·

It was a low-pressure water system, with water flowing

freely on a constant take-off principle, i.e. there were no storage tanks.

Overflow could be used for flushing sewers.

·

Settling tanks - piscinae - were used prior to final

distribution of the water. Just inside the walls of Nimes the castellum divisorium can still be

seen. This is a large circular basin

with a settling tank and a series of sluices and outlets by means of which the

water could be allocated as required to the municipal water system.

Some

praise of the Pont du Gard

Wheeler

“A triple arcade in perfect vertical proportion . . . Here we have the apotheosis of the arch, used with the functional good taste which was a Roman gift, and elevated to the level of an art.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

“These were the first Roman remains I had seen. I expected to find a monument worthy of the

hands that had made it, but for once the reality exceeded my expectations. It is the only time in my life that this has

happened and none but the Romans could have affected me this way.

The impression which this simple and noble work made upon me

was heightened by its situation. It

stands in the midst of a waste, whose silence and solitude make it more

striking and increase one’s admiration.

For this so-called bridge is in fact simply an aqueduct. One wonders what power transported those

enormous stones to such a distance from any quarry and brought the strength of

so many thousand men to a place inhabited by none. I walked through the three storeys of that magnificent work,

though reverence almost prevented my treading its stones underfoot. The echo of my steps beneath its immense

vaults made me imagine I heard the loud voices of the men who built it. I was lost like an insect in that

immensity. In spite of my sense of

smallness, I felt my soul to be in some way elevated, and said to myself with a

sigh, ‘If only I had been born a Roman!’”

AJ Sutton

‘A fusion of elegance and

practicability is to be admired’

From a tourist booklet by Yvette Goepfert & translated by Candice Richards

The aqueduct has a surprising lightness. Its beauty comes from simplicity and

grandeur. The stone is not sculpted and left in its rough state and only the

edges are cut to better join the blocks. The overall effect is to give the

ancient structure a relief rich in light and shadow. The conchitic limestone’s

warm colour suits the natural background and the bosses add ornament and

interest.