ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE - The Altar of Augustan Peace

Plate questions 1983, 1992, 1998

The Decoration

The Altar inside the

screen

A small frieze (39cm

high and 2.58m long) decorates the left side of the altar, representing a

procession to a ceremony of sacrifice, possibly the sacrifice made at the time

of the dedication of the monument in 9BC.

On the inside beneath

the spiral was a procession of Vestal Virgins.

The style of the two friezes on the altar is conservative, like earlier

republican ones rather than the great processions on the exterior of the

screen.

The interior walls of the screen

These are divided into two. The lower sections seem to have been carved to represent fence posts (possibly representing an earlier fence around the sacred site during the construction period). On the top half of the walls hang bulls’ skulls (bucrania), sacrificial bowls (paterae) and garlands of fruit. The fruit in the garlands represent all four seasons, reminding the viewer that Augustus’ power and peace spanned the whole year. There are palmettes between the two levels of the interior screen walls: these, together with the acanthus leaves, are evidence of Greek stylistic influence.

The exterior walls of the screen

It is divided along

its entire length into two – the lower and upper friezes.

The lower frieze

is the same on all sides, depicting elaborate floral designs of acanthus

plants. Amongst the vegetation are

swans, insects, snakes, lizards and frogs – all symbols of fertility and

reminiscent of 4th and 5th century Greece. Swans are also symbols of Apollo, the god

whom Augustus claimed supported him at the Battle of Actium in 31BC.

The upper frieze

is 1.55m high. The East and West panels contain sculptured reliefs containing

mythological symbolism, the longer South and North friezes depict the people in

procession in historical verism.

Details of the

decoration of the upper friezes on each face:

WEST FACE - the entrance flanked by mythological/historical scenes

A

l t a r

S

t e p s

Significance of the decoration on west face:

On either side of the entrance are previous leaders/founders of Rome, the details of whose existence are shrouded in myth.

Romulus founded the city of Rome and became its first king in 753 BC.

Aeneas led those Trojans who were left after their city had been destroyed by the Greeks to a new home in Italy. Romulus was descended from Aeneas.

The altar of peace, directly attributed to the actions of Augustus, is seen through the gap between these two early founders of Rome. They metaphorically embrace the third ‘founder ‘– Augustus, the bringer of peace.

EAST FACE - the entrance flanked by mythological/allegorical scenes

Tellus, (Mother Earth) or possibly Italy personified

is seated peacefully holding two plump babies. A cow and sheep graze contentedly

at her feet and there are luxurious flowers and fruit. Possibly the

personification of water and of air are at her side, one on a sea monster

and the other on a swan, or else fresh water is indicated by the jug on the

left and salt water by the waves on the right. This scene is allegorical of

fertile abundance and of the peace achieved by land and sea, for which

every Roman was grateful to Augustus. The armed goddess, Roma, is seated at peace, although

still armed. She is symbolic of Rome having conquered all and now wanting

peace, though prepared to fight to retain land won by war. The scene has been badly damaged.

Significance of the decoration on east face:

This side is allegorical of the peace, prosperity and fertility brought to Rome by the emperor Augustus. The twin babies and animals underscore his legislation encouraging the noble class to increase the population of Rome. Rome has control of earth and sea owing to Augustus’ achievements.

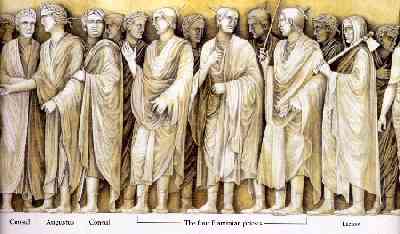

SOUTH FACE – Procession LEFT towards the entrance

People

are depicted processing on 4th July 23 BC towards the site of

the altar (the west). The emperor and his family are depicted, together

with other state dignitaries, in two planes, the principal characters to

the fore with the lesser participants all interspersed between them in lower

relief. It is thought that Augustus is depicted just

after the damaged section, with his toga over his head, indicating that

he is presiding over the ceremony as Pontifex Maximus – Chief Priest. He

did not in fact take this title until12 BC, after the death of Lepidus,

the previous holder. Note however

that he is presented as being first among equals ‘primus inter pares’, being

the same size as others in the procession and not repeated constantly on

the monument. Four flamines

(other priests) are identified by their hats with spikes, three flamines

maiores and the new priest of Julius Caesar (the last of them in the background).

Then probably follow Marcus Agrippa, who was Augustus’ son-in-law

and admiral, and the small boy, Gaius Caesar – Agrippa’s biological son

and Augustus’ adopted son.

The

lady is likely to be Livia, Augustus’ wife, followed by Tiberius, her son by a

previous marriage and eventual successor of Augustus. The two small children

are probably Antonia Minor and Drusus, other grandchildren of Augustus and the

woman in the background with her hand to her mouth is possibly Octavia, sister

of Augustus and wife of the late Mark Antony.

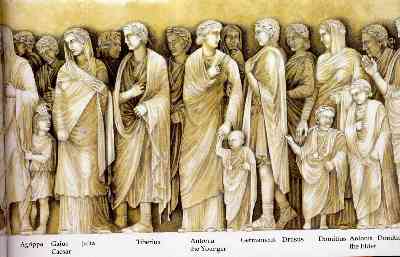

NORTH FACE – Procession RIGHT towards the entrance

Again

members of the imperial and of senatorial families, including children, process

towards the entrance. The inclusion of

children emphasises the message from the emperor that senatorial families

should be increasing in numbers. The

different height of the children and therefore of the folds of their dress adds

contrast, and a realistic three dimensional touch (also present on the South

side) is the extension of some sandalled feet over the edge of the level on

which the people stand. It is also realistic showing people in the crowd behind

the main characters and the varied directions of the gaze of the

participants. There is ‘visual variety and a rhythm that enlivens

and excites the eye; the procession vibrates with movement.’ This procession is clearly a family

gathering. There is the solemnity of a formal occasion, but also the realism of

children ‘playing up’.

Both North and South

friezes depict a leisurely procession, unhurried and orderly, but with many

people present. Three things are evident:

·

the

family is important

·

a

formal occasion requires reverence (pietas)

and quiet seriousness (gravitas)

·

the people in the

procession are recognisable individuals

Propaganda aspects of the Ara Pacis Augustae

·

The decoration on the

upper northern/southern exterior panels of the altar’s screen commemorates an

important state event – the procession in 13 BC to the site of the altar, to

give thanks for peace.

MESSAGE: Now Rome is at peace (after 100 years or

so of civil disruption and war) and you

have Augustus to thank for that.

·

The decoration on the

upper western exterior panels of the altar’s screen emphasises the divine

origin of Rome and of the Julio-Claudians, of whom Augustus was one.

MESSAGE: Rome has had a great history and it has been

favoured by the gods. Augustus, its ruler, is of divine origin and has family

connections which go back to Rome’s earliest days. He is a devout leader and is

part of the great destiny which the gods plan for Rome.

Augustus always stopped short of allowing himself to be regarded as divine, certainly in Rome. In far eastern provinces, where there was a tradition of rulers being regarded as gods, there occurs the beginning of Emperor worship, but elsewhere in the Empire, Romans were generally willing to regard leaders as gods once they were safely dead (remember what happened to Julius Caesar in 44 BC).

·

The decoration on the

left upper eastern and all the lower exterior panels of the altar’s screen

emphasises the theme of Peace (brought about by Augustus) and the resultant

prosperity and fertility.

MESSAGE: Rome now has the best possible conditions

(peace and stability) for all things to grow and prosper and you have Augustus to thank for that.

·

The decoration of the

interior of the screen emphasises the favourable relationship of Rome with the

gods (pietas) through worship, correctly organised and performed ceremonial and

sacrifice. This helps to bring prosperity and fertility to the nation.

MESSAGE: Now that

Augustus is the ruler (and leading by

example in paying due attention to the gods) you can have confidence that Rome is destined to be a nation which will

continue to flourish.

·

The fact that

children feature prominently on both the North and South friezes emphasises the

importance Augustus placed on the concept of family.

Augustus endeavoured to encourage the growth of senatorial families by passing laws giving

1. advantage to men standing for public office, if they had fathered children.

2. tax incentives for couples to have more than three children

3. penalties for men and women who remained single or childless.

Needless to say, people found ways to get around such legislation, which by its very nature of dealing with people’s private lives, is difficult to enforce.

MESSAGE: If Rome is to

flourish in the future as the gods intend, citizens are going to have to play

their part by strengthening the ruling families, as Augustus has pointed

out -

and

Augustus is father of his family (paterfamilias) and

father of his fatherland (pater patriae).

Sadly for Augustus he failed to produce a male heir himself. His first appointed heir was his nephew Marcellus, who died of ‘food poisoning’ while still a young man. Next appointed was Agrippa, his son-in-law, but being of similar age to Augustus, he predeceased him. Then two grandsons (children of Julia, his daughter, and Agrippa) became heirs, but they died accidentally too when young men in the Roman army. Augustus was forced to accept Tiberius, his wife Livia’s son from her first marriage, as his heir, and he indeed became the second emperor of Rome.

The structure as a

whole promotes Augustus’ imperial ideology on a scale and in a manner that is

unprecedented. He aligns himself with

historical realism in the North and South friezes, and with the mythological

symbolism of the East and West panels. The viewer is reminded repeatedly of the

greatness of Augustus and of Rome.

‘The Ara Pacis Augustae’ marks a turning point not only in

the artistic development of the Empire but also in the use of art for

propaganda. No Roman looking at the Ara

Pacis could have failed to be overwhelmed by a sense of relief at the passing

of the horrors of the Republican age.

He would have looked forward to a stable future secure in his belief in

the new leadership of the princeps’

(=Augustus). Source of quotation?